In Part I of this series, I discussed some of the most common misconceptions about the Bible in the secular world. This time, as the title indicates, I’m going to address some of the most common misconceptions about the Bible among Protestants. By “Protestants” I am referring generally to all Christian denominations that have developed since the Protestant Reformation. I know some people object to such a generalization, but for the sake of brevity it’s easier, and it’s not inaccurate; if you belong to any Christian sect that came into existence during or after the Reformation, it means you belong to a movement which began in protest of the authority of the Magisterium of the Catholic Church, and that your sect still “protests” this authority today.

Anyway, I realize that this post will likely be controversial to the Protestants who read it, but I want to say right at the outset that I certainly don’t mean this to offend or insult anyone — I’m attacking arguments and ideas, not people. I know that when someone claims that some belief you hold is wrong or illogical, it’s easy to take this as an implicit insult to your character, but I hope you don’t, because that isn’t my intention. This is all being said in good faith; like everything I write here, it’s about trying to help people move closer to truth.

So if you’re a non-Catholic Christian, thank you for your willingness to hear me out; I hope that this post will at the very least give you some things to think about. And if you have any questions about or objections to anything I say here, feel free to email me or message me on my Instagram page. You can also leave a comment below, if you’d like, and I’ll be happy to engage with you there.

Alright, let’s talk about what the Bible is not.

The Fullness Of God’s Revelation

As I’ve discussed in previous posts, God reveals aspects of himself to us through many different mediums — through all of Creation (i.e. the natural world), through the words of the prophets, through Sacred Tradition, through Sacred Scripture, and, of course, through Jesus Christ.

In many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets; but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world.

(Hebrews 1:1-2)

However, although God reveals himself to us through many mediums, Christ alone is “the Mediator and Fullness of All Revelation,” as the Catechism of the Catholic Church describes him. While everything that exists is really God speaking his Word to us in some way, he only speaks this Word fully and completely through the Person of Jesus Christ. And if Christ alone is the fullness of God’s revelation, it follows that the Bible is not the fullness of God’s revelation — God does not reveal himself fully through Scripture (nor through any of the other mediums I mentioned above).

You may wonder, though: even if Jesus is the fullness of God’s revelation, why can’t the Bible also be the fullness of God’s revelation? Couldn’t both Christ and Scripture communicate the Logos to us completely, if only in different forms?

I think the key to understanding why God’s Word cannot be fully expressed through Scripture is this: God’s Word — the Logos — is a Person, and a person cannot be fully expressed through writing.

That’s something to really reflect on.

The claim that the Word of God could be fully expressed in the pages of the Bible is — whether intended to be or not — an implicit denial of the Personhood of the Son of God, because a person cannot be reduced to words. I could write about myself for the rest of my life, filling countless pages with truths about myself; yet would the sum of all of this information fully communicate me? Would what I wrote be equivalent to who I am? And if a Person is how God has revealed himself to us, then in order for the Bible to be the fullness of God’s revelation it must completely convey the fullness of this Person — not only everything that he said and everything that he did, but everything that he is.

Is this the case? Obviously not.

This is clearly implied at the end of Saint John’s Gospel:

But there are also many other things which Jesus did; were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.

(John 21:25)

This is why the Bible cannot possibly be the complete Word of God or the fullness of God’s revelation to man. There must be more to God’s Word than what’s contained within the pages of Scripture, because God’s Word is a Person, and a person cannot be fully conveyed through writing. But what exactly are the practical implications of this? For starters, it means that the Bible is not the “end all, be all” that Protestants generally hold it to be. While it’s certainly a critically-important collection of writings, directly inspired by God in a way that nothing else is, the Bible is still just one part of the Christian faith, not the entirety of it, and not the foundation of it — which brings us to the next misconception.

Our Only Divine Authority

Most Protestants believe that the Bible is our only divine authority on earth. The general idea is that God has given us the Bible as our guide, so that we know what he wants us to do, how he wants us to live. They believe that the Bible contains all we need to know about God, theology, moral truths, and Christian religious practice, in order to attain salvation. Many also believe that this information is all plainly clear, enough so that one does not need the help of the Church, of theologians, of historians or biblical scholars, of anyone or anything else, in order to accurately understand it. In the standard Protestant view, the whole of Christian truth is found within the Bible’s pages and can be accurately understood by anyone, while anything outside of the Bible is non-authoritative and unnecessary.

Here’s one of the earliest official formulations of this doctrine, as found in the Lutheran Confession of Faith:

“We believe that the only rule and standard by which all dogmas and all doctors are to be weighed and judged, is nothing else but the prophetic and apostolic writings of the Old and New Testaments”

(The Formula of Concord, 1577)

Now, it’s important to say this up front: the claim that the Bible is our sole divine authority is directly and clearly contradicted by the historical evidence, which I’ll cover in a moment. But we actually don’t even need to look at the history in order to disprove the claim, because it fails on purely logical grounds.

The Logic

You see, if someone claims that the Bible is our only divine authority, our first reaction should be to ask how exactly we know that it’s our only divine authority. After all, it’s not like God just showed up one day, tossed the first Bible onto a table, and said that he wrote it and that it contains everything we need to know. And there are really only two possibilities: either God himself has told us directly that these specific texts are uniquely inspired and authoritative, or someone other than God has told us this, and that person or people must have been given the divine authority, by God, required to make such a declaration — otherwise their testimony would mean no more than anyone else’s.

However, if the Bible is our sole divine authority on earth then it means we must immediately throw out the possibility that anyone other than God has given us this information, because if the Bible alone has divine authority then some other person or people couldn’t possibly have the divine authority required to declare these texts to be divinely inspired.

So the only remaining explanation would be that God testifies to us directly that the books in the Bible are divinely authoritative. And because they’ve backed themselves into this logical corner, that’s precisely what Protestants try to claim.

Here’s one of the most common Protestant explanations for how we know which writings are inspired, as found in the Westminster Confession of Faith (1647):

“The authority of the Holy Scripture, for which it ought to be believed and obeyed, dependeth not upon the testimony of any man or Church, but wholly upon God, the author thereof; and therefore it is to be received, because it is the Word of God.” (Article IV)

“. . . our full persuasion and assurance of the infallible truth [of Scripture], and divine authority thereof, is from the inward work of the Holy Spirit, bearing witness by and with the Word in our hearts.” (Article V)

The biggest problem with such an explanation is that it isn’t empirically verifiable. If I claim that the Holy Spirit has testified to me in my heart that the Scriptures are of divine origin, there’s absolutely nothing that you or anyone can say or do to prove my claim false — but neither can it be proven true. It’s an inherently anti-rational explanation; you’re making a claim not only for which you have no proof, but for which no proof can possibly exist.

And what does it even mean to say that the Holy Spirit “bears witness in our hearts” that the Bible has divine authority? How would one know if this is happening? Is it just a feeling? What does it feel like? And why should such a feeling hold any weight? How would you know whether or not the feeling is truly from God? The fact that different people hold widely-varying religious beliefs should make you question your “feelings” about such things, because it’s safe to assume that most people feel that their own beliefs are true, whether they’re Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, etc.

As someone who has held different beliefs throughout my life about God and religion and the nature of reality, I can testify that I always felt like what I believed at the time was true, and yet many of the feelings that I had were eventually contradicted by later feelings. The fact is, our feelings are not objective markers of truth or reality, and there’s no objective test for determining whether or not our feelings are true or accurate in any given situation.

Of course, John Calvin, one of the big Protestant Reformers, claimed in his writings that “Scripture indeed is self-authenticated; hence, it is not right to subject it to proof and reasoning.”

That’s right, Calvin explicitly taught that it is wrong to seek proof of the Bible’s authenticity, and wrong even to use your reasoning when examining it. If you’ve read my past posts on the Logos, you’ll know that our ability to reason is divine, our rational minds are in essence a participation in the Divine Word, they are a gift from God which he gave us in order to help us discern truth. So Calvin’s claim is that in order to have faith in God and Scripture, we must deny our God-given capacity for rational thought — we must disregard our faculty for discerning truth in order to discern the truth. Do you see the problem?

Calvin goes on:

“Therefore, illumined by his power, we believe neither by our own nor by anyone else’s judgment that Scripture is from God; but above human judgment we affirm with utter certainty (just as if we were gazing upon the majesty of God himself) that it has flowed to us from the very mouth of God by the ministry of men. We seek no proofs, no marks of genuineness upon which our judgment may lean; but we subject our judgment and wit to it as a thing far beyond any guesswork!” (Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1.7.5)

I hope most people are immediately able to recognize that this is a lot of nonsense. Calvin says that we are able to “affirm with utter certainty” that Scripture is from God, with “no proofs, no marks of genuineness upon which our judgment may lean,” and indeed “neither by our own, nor by anyone else’s judgment” — which is a flat-out ridiculous statement to make. How could we judge that something is true without making a judgment? If you have concluded that something is true, it means you’ve made a judgment that it is true. Calvin seems to want to say that we “just know” that Scripture is from God because God gives us this knowledge in some mystical way, and he wants to bypass human judgment in order to reach a sort of perfect certainty, but this is impossible. Even if God directly placed some bit of knowledge within our minds, we are still the ones who would ultimately judge whether we accept it as true or not — you cannot escape the necessity of your own judgment when assenting to a proposition.

What both Calvin and the Westminster Confession are doing here is all too common in Protestantism; they’re attempting to take some traditional Christian belief and explain it without appealing to the actual tradition of the Church — without taking into account the history. And because of this, their explanations often end up being irrational and, at times, downright ridiculous. In this case, they’re ignoring the documented history of the development of the biblical canon, a history which shows us that the Bible is not and cannot possibly be our only divine authority on earth.

The History

As I mentioned in my previous post, the Bible is a collection of 73 books (though Protestants only accept 66 of these books, which is a topic for another time) written by many different people over the course of one to two millennia, and these texts were eventually assembled by the leaders of the Catholic Church into what we now call “the Bible”. But this didn’t happen in a vacuum; there are dozens, if not hundreds, of other writings from the centuries before Christ and shortly after his life which very much relate to the subject matter of the Bible, and which were widely read and cited by ancient Jews and early Christians, yet were not included in the biblical canon.

Here’s a list of non-canonical books which are nevertheless referenced in the Bible, and here’s a list of Jewish apocryphal texts.

Then there are writings from the New Testament era which were disputed in the early Church. These include:

- The Epistle of James

- The Epistle of Jude

- The Second Epistle of Peter

- The Second & Third Epistles of John

- The Book of Revelation

- The Gospel of the Hebrews

- The Epistle to the Hebrews

- The Apocalypse of Peter

- The Acts of Paul

- The Shepherd of Hermas

- The Epistle of Barnabas

- The Didache

This list comes from the historian Eusebius, specifically from his 4th century work Church History (which you can read in full here). As one familiar with the New Testament canon will recognize, some of the disputed texts he lists ended up in the Bible we now have, and some did not. So the main takeaway here is that in the early Church they didn’t have the clear-cut canon of inspired texts that we have today.

This was the case for the Jews in Jesus’ day, as well. Back then, there wasn’t a uniform “Judaism” like we might assume; the Hebrew people were divided into several different sects, with different beliefs and, most important for this discussion, different canons of Scripture. The main sects were the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Zealots, and the Essenes (though there were further divisions even within these groups), each of whom held somewhat different Scripture canons. It was generally agreed upon by all Jews that the Torah, the first five books of the Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy), were Sacred Scripture, but beyond that there was no set list of inspired texts.

The point I’m driving at with all of this is that someone, somewhere in the history of Christianity eventually made the decision that there are certain texts from among a multitude which are uniquely inspired by God, and that these certain texts should be set apart from the rest.

This first happened in the late 4th century, and the same canon was reaffirmed many times after.

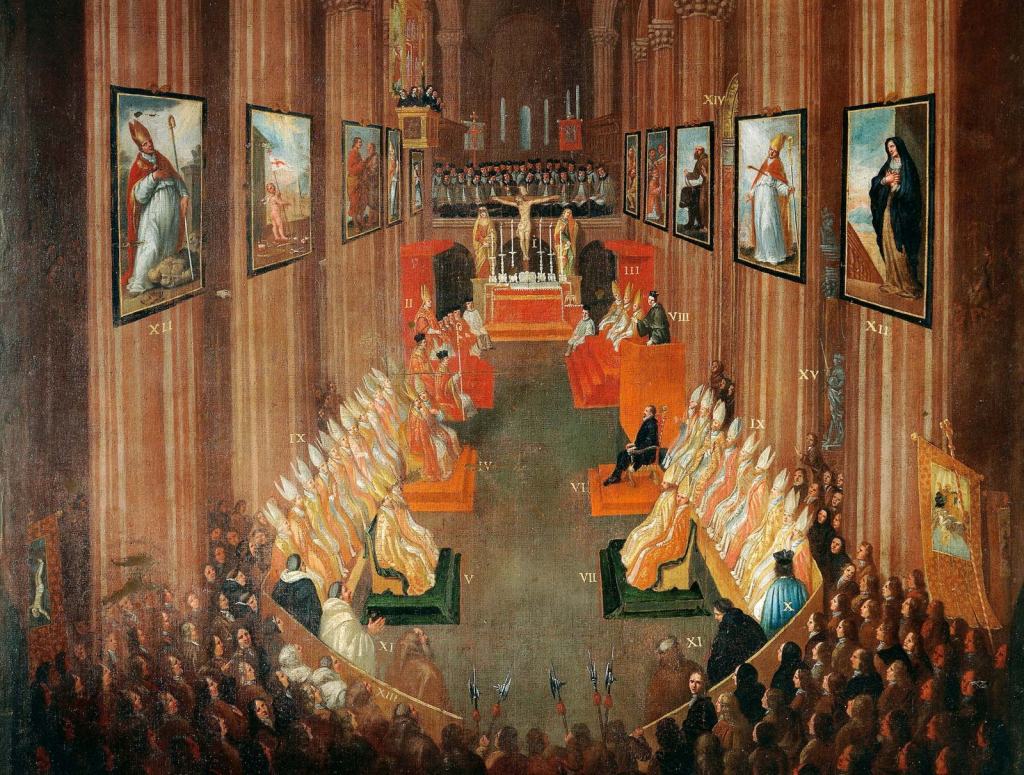

- In 382, Pope Damasus convoked the Synod of Rome which published a list of inspired texts identical to the canon of the Catholic Bible.

- In 393, the Council of Hippo reiterated the list

- In 397, the Synod of Carthage also reiterated the list

- In 405, Pope Innocent I wrote a letter to Exsuperius, the bishop of Toulouse, listing the same books as Scripture

- And the same list was reaffirmed in 419 at the Second Council of Carthage

- In 797 at the Second Council of Nicaea

- In 1442 at the Council of Florence (Session 11)

- In 1546 at the Council of Trent

- And in 1870 at the First Vatican Council (Session 3, Chapter 2)

Each of the decrees and councils provided the same list of inspired texts, and no council or papal decree has ever given a different list.

(If you’d like a more detailed history of the development of the biblical canon, this article gives a great summary.)

So, we have Eusebius writing in the 4th century that there were still disputed texts, indicating that an official canon had not yet been declared. Then, towards the end of that same century, we have multiple councils/synods that begin to make official declarations about which books are inspired. So our historical records clearly show that the leaders of the Catholic Church set the canon of the Bible. And the only reason the testimony of the bishops at these councils actually mattered is because they possessed the authority needed to make such a declaration — divine authority, which had been passed on to the Apostles by Jesus Christ himself, and then passed onto their successors through the generations (a topic which I’ll cover more soon).

I want to be clear, though: I’m not saying that these bishops gave the Bible its divine authority. Rather, what I’m saying is that our knowledge of the divine authority of these specific writings depends on the testimony of these bishops. I’ve often seen Protestants try to claim that Christians simply knew from the beginning which texts were inspired by God, but as Eusebius makes clear there were several texts whose divine status was disputed for the first few centuries — which proves not only that claim wrong, but also the claim that the Holy Spirit testifies to each of us individually about which texts are inspired. This clearly wasn’t an experience that Christians in the early Church had, or there would have been no disagreement on the status of certain texts.

No, the fact is that the disagreement was settled by the bishops of the Church; they are the ones who officially declared which texts were inspired and which weren’t, which means that our knowledge of the divine authority of Scripture depends on their testimony. And if our knowledge of the divine authority of Scripture depends on the testimony of men, then those men necessarily must be speaking with divine authority. Otherwise, our knowledge of the divine authority of Scripture would be fallible, because it would depend on the testimony of regular, fallible men, who have no more authority to speak on divine matters than you or I do, and so their testimony could not be believed with religious assent. And this is why the Protestant claim fails. The Bible cannot be our sole divine authority on earth, because if it were, we wouldn’t be able to know with religious certainty that it has divine authority.

In Conclusion

There’s much more to be said about these topics, but this post is already running a bit long so I’ll leave it here for now. I sincerely hope that what I’ve shared will be helpful to you, whether you’re a Catholic, a Protestant, or neither. For as much as Protestants value the Bible, they nevertheless have some fundamental misconceptions about it. The reality is that trying to hold onto certain Christian beliefs while disregarding the foundation of those beliefs — the history, tradition, and authority of the Church — forces them into coming up with ad hoc explanations that often contradict facts, logic, or both. True Christianity is deeply rooted in history and reason; since returning to the Catholic faith, I’ve been astounded at how different it is from the “popular” form of Christianity that most of us are familiar with — which is very Protestant, ahistorical, and often irrational.

The Bible is certainly a unique and important aspect of the Christian faith, but it does not contain the fullness of God’s revelation to man, nor is it our only divine authority on earth. Hopefully I’ve done a decent job at explaining these points, but as I said in the beginning you should feel free to contact me if you have any questions or anything you’d like to say in response.

God love you.

2 thoughts on “What the Bible is Not, Part II: Protestant Misconceptions”