When we look at the world, what do we see? We see sense, as in we can make sense of things. The very fact that we can make sense of the world means that it must necessarily be sensible. From particles, to plants, to planets, everything in existence is structured in a certain way and behaves in a certain way. The natural world is ordered, but is this order arbitrary? Are things arranged the way that they are without reason? Or is there intelligence in the order? Are things structured the way that they are for a purpose? Do they behave the way that they do for a purpose?

What Apple Trees Want

If I see an apple fall from a tree and ask you why the apple wanted to be on the ground, you could rightly correct me and say that the apple didn’t want to be on the ground, it was simply obeying the law of gravity. But that’s far from the whole story.

In truth, the apple fell to the ground for a purpose: apples contain seeds, and in order to make more apple trees the apple seeds must find their way into the soil. This can happen either by an animal eating the apple and passing the seeds onto the ground, or by the fallen apple simply decaying until the seeds are exposed to the soil. But either way, the apple being on the ground makes this process quicker than if the apple simply stayed on the tree.

So really, the reason why the apple fell was because the apple tree ‘wanted’ to make more apple trees. But for a thing to ‘want’ — to have aims — and to direct its own actions towards those aims, it must have intellect and will; that is, the power to think rationally, and the power to choose its actions freely. Apple trees have neither of these. But if the apple tree cannot be ‘aiming’ its own actions towards creating more apple trees, then who is directing its aim?

Darwinism & Infinite Robots

Today, many will try to claim that there doesn’t need to be a ‘who’ behind these sorts of natural processes. They say that Darwinian evolution/natural selection has shaped the apple tree and formed it over time to propagate itself efficiently. But this is no explanation at all, because it’s simply pushing the question back one step — who then designed the process of natural selection to work the way that it does? Simply appealing to natural selection as an explanation for the apparent intelligence behind the processes of nature isn’t helpful, because natural selection doesn’t possess an intellect or will either — it’s as mindless as the apple tree.

It’s like if I asked you who made your car, and you said that there wasn’t a ‘who’ because it was assembled by mindless factory equipment. Okay, but then who designed the factory equipment? The car has clearly been designed by a mind; there is reason, rationality, in the structure and function of it, so it necessarily must be the product of an intellect, regardless of how far removed that intellect is from the final product.

Even if mankind were to build robots that could build more robots that could build more robots, creating a self-sustaining robot population, this process couldn’t have begun without the intellects of the human beings designing it in the first place; their intelligence is present as a necessary component of the entire process. You cannot have an infinite regress of unintelligent robots creating more unintelligent robots, because they’re behaving intelligently — you have to explain where the intelligence in the process came from.

This is no less the case with the natural world. There is intelligence in the process of an apple tree making more apple trees, yet nothing involved in this process possesses intelligence, itself. The intelligence is built in to the nature of the apple tree, and we have to explain how it got there.

It’s also crucial to recognize that this phenomenon where objects behave intelligently, acting toward an end or goal, isn’t just a characteristic of living things; it’s also a characteristic of non-living matter. Electrons, for example, are naturally inclined to bond with protons — this is their aim. And if this wasn’t their aim, if they weren’t naturally inclined to bond with protons, then we wouldn’t have the elements, the very building blocks of matter.

Evolution and natural selection do not apply to electrons and protons, because they aren’t alive; in fact, the process of evolution itself depends on electrons being naturally inclined to bond with protons. If these particles didn’t have the natures that they do, with the aims that they do, then the process of biological evolution never could have come about because no physical matter could have come about. Natural selection depends on the non-living building blocks of the physical world behaving rationally, and being naturally oriented toward specific goals.

Word, Wisdom, Reason

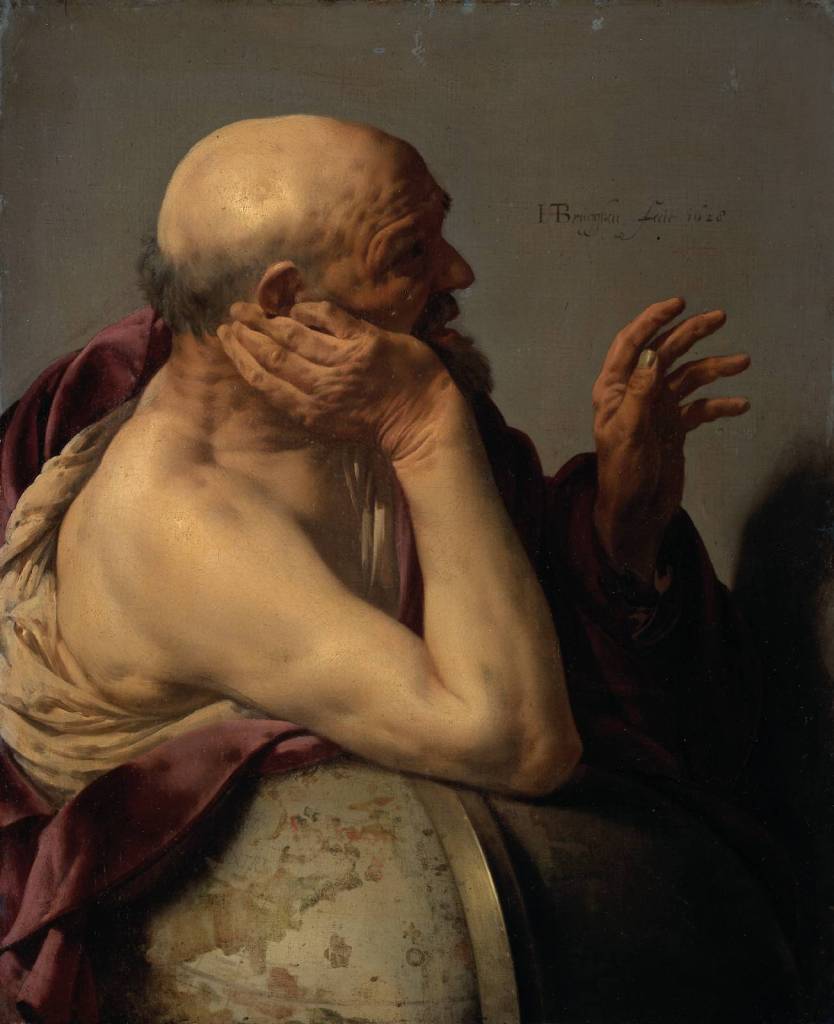

Alright, so what does all of this have to do with Logos? Well, in the 6th century B.C. there was a philosopher named Heraclitus of Ephesus, and he too recognized the intelligence that’s implicit in the operations of our world. Heraclitus called this intelligence “The Logos”.

If you read my post on Agápē, I very briefly mentioned that the Greek term Logos can be translated into English as ‘Word’, ‘Wisdom’, or ‘Reason’ — but there’s a bit more to it than that. The term Logos doesn’t have an exact word-for-word English translation which contains all the complexities that the concept held in its original Greek. So to help us fully understand the concept, we need to look at what exactly the terms ‘Word’, ‘Wisdom’, and ‘Reason’ mean.

‘Word’ can be defined as “the expression of a thought or idea, written or spoken.”

‘Wisdom’ can be defined as “the ability to discern or judge what is true, right, or lasting; insight.”

‘Reason’ can be defined as “the ability to think; intelligence.”

As you can see, these terms are all very much related. Our ability to reason is what allows for our ability to speak and write words, as well as our ability to gain wisdom, to discern or judge what is true and right. All of these concepts are contained in the term Logos, so the most accurate translation of the term would be something like “the intelligent expression of a thought or idea that is true and right.”

The Riddler

Now, logos was a common word in ancient Greece, but only in reference to expressions of ideas by human beings. It wasn’t used to describe the intelligence within the processes of nature; as far as we can tell, this use of the word originates with Heraclitus. In fact, much of Heraclitus’s thinking was revolutionary, which is why so much of it was misunderstood during his time. He allegedly earned the nickname “The Riddler” because his ideas were so difficult for people to make sense of, and he would use short aphorisms to convey very complex ideas, such as, “If all things were turned to smoke, the nostrils would distinguish them,” and “On those who enter the same rivers, ever different waters flow.”

Fortunately for us, though, many of his sayings are clearer than these, and several relate directly to his Logos idea. He apparently only wrote one book, of which we possess no copies today, so all that we know about him actually comes from fragments of his ideas and sayings that have been quoted in the writings of other philosophers. We’re told that his book began with the following paragraph:

“Though this Word (Logos) is true evermore, yet men are as unable to understand it when they hear it for the first time as before they have heard it at all. For, though all things come to pass in accordance with this Word, men seem as if they had no experience of it.”

Note that Logos is translated as “Word” here, and this is likely due to context clues; Heraclitus talks about hearing the Logos, which indicates he’s referring to a spoken Word, at least in a certain sense.

Here are some more of his fragments that should be helpful for our purposes:

- “For this reason it is necessary to follow what is common, but although the Word is common, most people live as if they had their own private understanding.”

- “They are at odds with the Word, with which above all they are in continuous contact, and yet the things they meet every day appear strange to them.”

- “Divine things for the most part escape recognition because of unbelief.”

- “Human nature has no insight, but Divine nature has it.”

- “A man is called infantile by Divinity, as a child is by man.”

- “For all human laws are nourished by one law, the Divine law; for it has as much power as it wishes and is sufficient for all and is still left over.”

- “Wisdom is one thing. It is to know the thought by which all things are steered through all things.”

So, what can we gather about the Logos from all of these fragments?

All things come to pass in accordance with it — it governs the entire world.

It is true evermore — it is the unchanging standard of objective truth.

It is common — all things share it, all people have access to it.

People are in continuous contact with it.

It is like a Divine Law.

Yet most people evidently don’t understand it, and are even at odds with it.

But people could recognize it if it weren’t for their unbelief.

And wisdom is “to know the thought by which all things are steered through all things”, which is referring to the Logos — to be wise is to know the Logos.

Obviously this is still pretty abstract stuff, but hopefully you’re beginning to grasp the concept a bit more fully. What might be helpful, though, is an analogy.

Hearing the Word

As I touched on already, intelligence can only come from a mind, which means that a logos — an intelligent expression of an idea that is true and right — can only come from a mind. So it follows that if there’s a Divine Logos, there must necessarily be a Divine Mind that is expressing this Logos. And recall that Heraclitus talks about us “hearing” the Logos. So then it seems as though the Intelligence that structures and governs the universe is, according to Heraclitus, nothing less than the Divine Mind speaking. All that exists in the cosmos is formed and guided by the Divine Word, which is the source of all reason, truth, and wisdom.

Now, as I said, this is ultimately an analogy; there isn’t a literal word being spoken that we can hear. But it’s quite an apt comparison, and what a beautiful and profound idea. When we study the world, we aren’t just discovering and observing dumb facts and information, we are discovering a Logos, an intelligent Word, which is the expression of the Wisdom of the Divine Mind. All of science and philosophy can be seen as our attempts to understand what the Intelligence behind the cosmos is communicating.

Yet Heraclitus was quite clear about his belief that many if not most people don’t understand the Word, the Wisdom that the Divine Mind is communicating. It’s as if the Logos is being expressed in a language that we do not natively speak, and so we cannot comprehend it unless we make an effort to learn how. But why is this the case? If the Logos is what structures and governs all that exists, doesn’t that include us? Aren’t we as much products of this Divine Word as anything else? So then why the disharmony? If we were ‘spoken into existence’ by this Divine Word, then shouldn’t the Divine ‘language’ be our native tongue, so to speak? I’ll have to leave this issue be for now, because it’s too tangential to our current subject matter, but I will say that Catholic theology provides an answer to this question that’s quite compelling, and I plan to cover it in a future post, so stay tuned for that!

For now, though, let’s simply accept the reality that we cannot naturally understand the Divine ‘language’ on our own. How might we remedy this? When we want to learn a new language, what do we do? We look to someone who knows both the language that we’re hoping to learn, as well as our current language, so that they can translate the foreign language into our own. So it seems as though the best possible way for us to learn the Divine ‘language’ would be for this Divine Mind to translate it for us.

Well, believe it or not, that’s exactly what happened. About five centuries after Heraclitus lived, the Divine Logos was finally ‘translated’ for all of mankind. This event is what the Church refers to as The Incarnation, which occurred when, as Saint John the Apostle so poetically puts it:

“The Word became flesh, and dwelt among us…”

(To be continued in Logos, Part II)

God love you.

5 thoughts on “Lógos, Part I”